and Live at Lightening Creek

I was quite ill with cramps on our way from Sanford to Durango. We traveled in company with two Hostedar boys who had recently been to the Manti Temple and married two sisters by the name of Martensen – Emma and Rigley. There was also an Englishman, an old bachelor of a not too good a reputation. His name was Fred -----.

It took us some days to travel that 200 miles from Sanford to Durango. When we got there they all went to work on the new railroad grade, an extension from Durango west. We pitched our tent near the camp of 200 men who were working on that same road. Emma Hostedar and her husband pitched theirs about 100 yards from ours under a great pine tree.

One day just after dinner when the men had all returned to work, an awful electrical storm came; the thunder was almost [Page 96] deafening, and lightning flashed in all directions. Emma ran over to my tent crying, I walked back and forth on the tent floor wringing my hands saying over and over again, “Oh Lord save us.” I kept this up. Emma laughed, then cried, and kept on laughing and crying. I stopped suddenly and said, “How can you laugh and cry at the same time?” She said, “Your behavior is so amusing and this storm so terrifying I just can’t help it.” I stepped to the tent door, just in time to see the lightning strike a great pine tree, a short distance away, about one-third distance from the top, which crashed to the ground, while the trunk was split in two pieces.

The railroad grading was too hard for our teams. The company had a boss who carried a great whip, and as the teams passed they felt its force. My husband could not stand that so he secured a job farther down the canyon, about five miles from Durango hauling coal from the mine and delivering it in town. Chester Hosteader got a job hauling ties.

The other brother, Nephi Hosteader got a job near the mine and lived near us the rest of the summer. A Mr. Erickson, a Mormon, also had his tent near ours.

The railroad company had built a double grade beside our tent. The highway was just beyond the double grade and next to a high mountain. The coal mine was about a quarter of a mile below our tent, and they were building a grade on the side of the mountain above our tent, to the mouth of the mine, and on that grade they were blasting several times a day, and we had to be on the look-out and when the signal was given, I had to take the children and run and hide behind piles of ties, while the shower of rocks from the blast passed over our heads.

The children had a great time that summer digging tunnels, and building little railroads just back of our tent. There were hundreds of men working around us every day. One day little Ida was very ill, and the noise of the workmen was terrific. Ida said many times that day, “Oh mamma, do tell them to please keep still.”

There were two other men who hauled coal to town and they wanted to have their noon meal at our house, or tent, so I tried it for a month but there was nothing gained, so I quit.

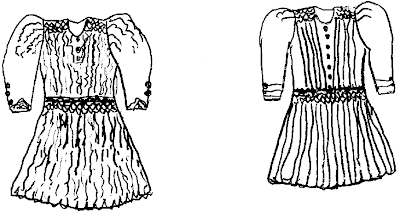

The bakers and bosses at the R. R. Camp begged me to do a little washing for them. They changed underwear several times a week, and I charged them from 10¢ to 15¢ for each article, though [Page 97] most of them were scarcely soiled, and I soon had quite a few dollars piled up, and during September my husband suggested that I buy with my money winter clothes for the little girls and myself, and he would buy for himself and little B. F. So B. F. got a new suit (his first boughten suit), a coat with two pairs of pants, shoes and other things; while I and the girls got beautiful wine colored flannel for dresses and material for wraps, underclothing and shoes.

I made those little dresses something like this: Honey-combed shoulders and skirt.

The mine was on the left side of the canyon going toward Durango, about five miles from town. It was up from the canyon floor about 125 feet. The great tunnel ran straight through the mountain with continuous rooms on either side. Then on the opposite side of the mountain the cars went over trussel works which bridged a canyon and then into another tunnel straight into the next mountain. The mine was closed for a while during the time we were there and a notice was posted up that visitors were not allowed, but the mine boss who had a lovely home down the canyon, had no children, and took such a liking to our Lottie he told her she could have a pass for our family any time she liked. One day when we visited the mine, the workmen had come to a petrified pole while raising the roof of the tunnel, and were care- fully trying to take the pole out whole. The tunnel was 1900 feet straight through the first mountain, and when you were half way through you could see light at either end about the size of a pin head. [Page 98] There was a large mine hotel, and a separate large sleeping house for the miners on the mountain side, on the opposite side of the canyon from the mine. The lady who ran the boarding house was extremely kind to us. She often came to see us and whenever the miners wives came on a visit she brought them down to see our little family. She was so thoughtful of the children. They had two fine Holstein cows, but bought canned milk for most of her cooking; several times each week she brought fresh milk and said “these little ones must have fresh milk.” We were surrounded with a conglomerate mass of humanity. When we first came there my husband told me to cover our garments whenever I hung them to dry, and we would say nothing about being Mormons. We followed that advice but in a very short time every body knew we were Mormons. The horses got distemper, and one Sunday afternoon my husband brought the horses to the tent door, put their blankets over their heads, took a shovel of coals and poured some kind of horse medicine on the coals and asked me to hold the shove while he held the horses, to let them inhale the fumes. Men were leisurely strolling around, and before we were aware, quite a group had assembled on the highway 100 yards away. They were looking straight at us. One man asked “What on earth are they doing?” Another man said, “It’s some Mormon charm they are working.” After meals when my husband went to the coal shoot to get his wagon he often put the children on the horse’s backs and let them ride. I walked along to bring them back. One gruff old fellow working nearby sometimes said, “Governor, I would hate to be you and have a bunch of kids to bother with.” There was a Mormon man by name of Erikson lived in his tent not far away. One day when I was crocheting I got up to do something, when Baby Enoch who was on the bed where I laid my croquet work, he got hold of the hook, and stuck it in his eye. There were a few threads of wool from the quilt which were still in his eye ball; when I pulled it out a little blood oozed out. I sure was frightened. I ran with baby to Mr. Erickson’s tent to see if he could tell me anything to do. He said, “Just be calm, I think it will be all right.” While I was crocheting little Ida begged me to let her try. She was between 5 and 6 years of age, yet that sweet little soul crocheted a nice edge on underslips for herself and Lottie and one for me. [Page 99] I had always thought that polygamous wives had great trials but I found that their trials were not be be compared with the trials of women whose husbands were untrue to them. One of the miner’s wives while wringing her hands and crying told me her life’s story. She had come to stay with her husband and they had a large lovely tent, and furniture too. She told me to come and use her machine when ever I had sewing to do. She was a native of Iceland a very fine woman. One day when I came over to sew, I found her lying on the bed, she seemed to be in great agony. I asked if she was ill. She said, “Oh no, good lady.” I sat down to sew. She seemed convulsed with pain. I went to her and asked if there was anything I could do for her. She said, “No.” She groaned, got up, wrung her hands, cried, lay down again and groaned. I put my arms around her and said, “Oh please let me help you.” Then she asked “Does your husband drink?” I told her no. She said, “Then you don’t know what I suffer today.” She said, “My Freddy got his month’s pay last night, and he has gone to town. And oh, good lady, I don’t know when he will come back, nor where he will go while he is away.” She said she had married Freddy because she loved him so. They went to New Mexico and went into the hotel business, made lots of money every month, but Freddy spent it all in bad ways. They sold their hotel, and tried other things, but the money went the same way. Finally they came here, she hoping things would be better but now Freddy was in town, perhaps intoxicated, and the town was full of corruption. The largest house in town was the gathering place and dancing quarters of bad people, and Freddy was liable to be there. This time Freddy returned earlier than usual, and her happiness knew no bounds. The evening after Freddy returned, my husband and I went over to their tent on an errand. Freddy offered my husband a drink; my husband said, “Thank you, I never drink.” Then she passed him a box of cigars. My husband said again, “Thank you. I never smoke.” They were both astonished. She put her arms around her husband and said, “Oh Freddy, Freddy, just look at this man who neither smokes nor drinks.” Blue jay During our stay at Lightning Creek, as the canyon was called on account of the fierce electrical storms which often passed over the place, Nephi Hosteader was sometimes out of work, and on such [Page 100] occasions he would take little Bent F. with him trapping small animals up and down the great wash which ran the full length of the canyon and carried off the flood waters when the storms came. He also shot birds, bluejays, very often. A taxidermist lived near and the bluejays were so pretty, and I was wishing I could have one stuffed so I could take it home to Utah with me. So he taught me how it was done. Nephi carefully killed one for me, and though I had no chemicals, I proceeded without them and stuffed my bluejay, and brought it home to Utah and kept it for a long time. Bears One day over the mountain from our tent, a mother grizzly bear attacked a man, knocked him down and began chewing his arm. The man fainted. And when he came to the bear was a short distance away going in the opposite direction where she had left her cubs. The man dared not move until the bear went out of sight. Then he crawled for some distance, and as his strength returned sufficiently he arose and went as rapidly as possible to the tie camp. Men rushed to the place where the bear attacked. There was the bear with her cubs. They were soon dispatched and the man taken to the hospital. Another morning as the men went down the grade half mile from our camp they met a grizzly coming up the canyon. They ran back for guns, but when they went back Mr. Grizzly had disappeared. There was a U. S. Soldier fort, about eight miles from our camp. Every night and morning we could hear the bugle call. Each month a group of soldiers with their officer came down the canyon past our tents on their way to Durango to escort the pay car to their camp, and as they neared our tents the bugler would play a tune. The officer gave commands and the group of soldiers would go through some fine maneuvers, some fancy military stunts for our benefit. It was surely interesting. In this fort the U. S. troops were exchanged while we were there. They were sent to the East, and a group from Brooklyn, New York, were brought to their fort. This company came marching right by our tent on the railroad grade, four abreast. Baby Enoch was playing near the tent door and as the great group was passing I heard some one talking in very [Page 101] gentle tones to baby. I came immediately to the tent door, and there was a trouper on one knee beside my baby, talking in such loving tones to the little tot that it was quite touching. On seeing me he arose and bowed saying, “How do you do, Mother.” As the last of them passed I came out and watched them marching down the grade, and thought it was a very pathetic sight. I thought if I had a son in a group like that marching off to war it would almost, if not quite, break my heart. In a few days the Brooklyn group came by. We had a feed box for the horses’ grain about 20 feet from the tent door, the box was securely nailed onto two posts which were set in the ground, and the box was just high enough so the horses heads came even with the box. When the horses were away, dozens of chipmunks, little ground animals, ran up and down those posts filling their pockets with grain. When the Brooklyn group came, the ladies, I suppose they were officers wives, came in carriages and when they came even with the feed box they stopped, saying, “Oh look, see those funny little animals. Oh just look, I never saw anything like that in my life. What are they, and what is that box up there for?” Oh said one, “That must be their hotel.” The body of troops soon came by, marching four abreast again. And as they were passing a shout went up, “We have got a new recruit! We have got a new recruit!” Men’s laughter followed. I stepped out to see what it was all about, and there was my baby toddling right off among the men; he had gone at least 25 yards along-side of a big fellow, amid the shouts and laughter of all the men.

No comments:

Post a Comment